-

Exploring the best podcasts on urban affairs

A brief review of the best podcasts focusing on global urban affairs and city diplomacy.

By Emanuele Sala

“Sometimes reality is too complex. Stories give it form.”

Director Jean-Luc Godard reiterates that stories are vital to human beings. Podcasts are a contemporary form of educational stories: their success in terms of listeners and initiatives confirms our fascination with this narrative form.

In this connection, the podcast format is not only entertaining but taking on an increasingly important role as an information output for both academia and business. This product could impact education and learning and bridge academic research and wider public dissemination. A success due to the low-cost and accessible form of expression that the podcast ensures. Unlike other media, it can guarantee greater representativeness to different urban actors. It is a valuable opportunity also for the domain of city diplomacy, still often overlooked by standard academic works.

With this brief general review of quality podcasts dealing with urban issues, we also want to highlight their focus on city diplomacy through specific episodes or an editorial approach based on the exchange of best practices and knowledge. It is not a thorough review, but it serves to give an idea of what the market can offer today.

The classification followed is based on the criteria of podcast dissemination. Thus, what is the central targeted public of a podcast? Following this criterion, we recognize three podcasts’ categories: those addressing the general public, dealing with general and broad urban matters, those for students and scholars, and those targeting city practitioners and enterprises about more specific and operational issues.

Podcasts for the general public

Monocle 24: The Urbanist

With more than ten years on the show, The Urbanist, by the radio Monocle 24, is one of the most well-known podcasts on urban affairs. It tackles broad topics and claims to have an influential audience of mayors, architects, and urban planners. The few-minute cycle of episodes “Tall Stories”, released weekly, offers fascinating insights into the best planning examples and sound management practices around the world. It is as entertaining as it helps promote the exchange of best policies in cities. “The Urbanist” weekly series consists of 30-minute episodes that address key topics. Two episodes highlight the peculiar relationship between certain cities and their diplomatic importance. In the episode Placemaking, Biodiversity and Diplomacy, we find an innovative insight into the urban dynamics that New York City faces when it becomes the stage for international diplomacy. The same relationship is addressed by Power City, on how the design of some cities (Washington, Brussels, Vienna) changes because of their diplomatic importance. It is an original perspective on how some cities relate to global affairs.

360 Degree City

360 Degree City is a bi-weekly podcast by Californian Intelligent Futures that aims to highlight the steps of the actors that make cities better, and to change the point of view of its users about their city. The title emphasizes the complete vision that the audience must receive, 360 degrees. In this regard, the cycles “City Builder” and “What’s next” are two original contributions. The first one analyses the main actors that make cities. Thus, we find interviews with elected officials, architects, urban planners, transportation and civil engineers, etc. The second cycle asks questions about the urban future in various fields, such as housing, mobility, supply chain, and urban communities. Interestingly, Intelligent Futures intend to investigate the larger global system of which cities are part. The episodes address different scales, making evident the connection between all cities and their influence on the others. “Our guests,” the organization reports, “explained how cities connect to these systems and also how there are sometimes disconnects with how we understand how our cities relate to the world”.

Strong Towns

This podcast has been running weekly for more than ten years, and it deals with urban issues that are less generally discussed. The podcast addresses not only infrastructure, transportation, housing, smart cities, etc., but also the role of popular traditions, daily life, or grassroots movements in creating the city. Even though the theme of collaboration between cities is never explicitly addressed, the focus on grassroots movements gives the idea of a global system of cities facing the same challenges and opportunities. In the long episodes (an hour on average), participants include experts from business and academia, but citizens and their experiences above all. The podcast is part of a triptych of Strong Towns, the homonymous organization. Completing this three-part set are the podcasts The Bottom-Up Revolution, which deals explicitly with grassroots movements in cities, and Upzoned, which focuses on major debates in urban studies. The association’s main goal is to raise awareness about what a strong city is and advocate for policies that make cities better.

Urban Matters

The Urban Matters podcast is produced by the UNECE (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe). Its episodes cover topics of different scales and scope – from the functioning of the Forum of Mayors, the event gathering mayors of cities in UNECE countries to fire safety in urban buildings, passing through housing, circular economy, and smart cities. Hosted by journalist Tom Miles, with contributions from experts, academics, and practitioners, it always retains a view on how cities can join forces to share ideas and grow together, to combat not only pandemics but also other ills that plague urban societies.

Podcasts for an academic public

The Cities of Refuge

The Cities of Refuge is primarily a research project based at the University College Roosevelt, exploring the role of local governments in Europe in welcoming and integrating refugees. From a law perspective, the unit is researching the relevance of the local dimension in this global matter, adopting a new insight on the role of cities. The homonymous podcast focuses on this same theme and offers unique contributions to city diplomacy about migration. For example, the podcast offers an original view on the relationship between cities and international law, finding a position for an often overlooked subject in international relations. Another recent contribution to the domain is the episode on city diplomacy in global migration governance. Through the insight of two researchers in the field, the episode investigates the international stance of cities to promote specific priorities in the global agenda or to attract funds to the local level in the challenge of migration management. The episodes are generally aired twice a month.

Connected Cities

Started as an initiative of the Melbourne Centre for Cities at the University of Melbourne, the Connected Cities podcast began in the period immediately preceding the Covid-19 pandemic, with a variable schedule. The typology of the episodes is twofold. On the one hand, recordings of debates between academics and researchers on various topics, such as the role of cities in the fight against pandemics, housing, and sustainability. On the other hand, individual interviews deal with a specific theme in a shorter duration. For example, the podcast has addressed the issues of night economies in several episodes, offering valuable insights into the functioning and management of the night in the city. The podcast also devoted many episodes to the COP26, focusing on the role of cities within this framework. The focus on urban observatories about the pandemic concentrates on global relations between cities in the fight against the pandemic.

Urban Political

Urban Political is an academic podcast hosted by Ross Beveridge (University of Glasgow) and Markus Kip (Humboldt University in Berlin). The Georg-Simmel-Center for Metropolitan Studies at the Humboldt University powers the initiative to allow the voices of scholars and activists to be heard and be part of a transnational debate. As the name suggests, this podcast deals with a wide variety of urban issues. From social housing to tourist gentrification, from metrolingualism to troubling urban graffiti. The specificity of the podcast is that it deals with topics relevant to research in urban studies. The podcast aims to connect urban activism and scholarship, where each episode offers snapshots of pressing issues and new publications, allowing multiple voices of scholars and activists to enter into a transnational debate directly. The long episodes, issued irregularly, are one hour long.

Podcasts for experts and city practitioners

Smart and Sustainable City

In this 30-minute podcast Pierre Mirlesse, the podcast host, interviews key people in organizations who are shaping the smart city field. These actors tell about the reasons that lead them to establish or work in a specific activity and its importance in implementing smart city policies. Experts and organizations come from both the private and public spheres, with episodes focusing on the European Commission, the World Bank, UNECE, or private companies such as BP, Deloitte, and OASC. Experts also come from local governments, as for the coordinators of smart city programs in Copenhagen or Barcelona. The podcast is a product without frills, which remains a valuable tool for understanding the activity linked to smart policies. However, it often favors an internal point of view and promotes a specific business vision. The podcast was interrupted in August 2021.

Energy Cities

This monthly podcast builds upon interviews with actors operating in cities as part of the promoting organization Energy Cities Network. It deals with sustainability and clean energy issues, collecting opinions and points of view of city actors, academics, and managers. It is a valuable tool for evaluating good practices related to specific urban energy policies. The Energy Cities Network gathers one thousand members, all cooperating to build future-proof cities. A related strength is the broad scope of cities involved, including global, medium, and small cities. As a means to inform about the steps undertaken by the most active and ambitious members, the podcast could be a valuable tool to help cities in the energy transition.

Connected Places

The Connected Places podcast is promoted by the Connected Places Catapult, a U.K-based innovator which reflects on and offers solutions linked to mobility. The podcast itself addresses topics of connectivity, understood in a broader sense. The connectivity could be physical, social, or digital. By employing and developing the full potential of all three types of connectivity, the organization wants to help create better cities and prosperity for its citizens. Therefore, the podcast deals with mobility issues, but in its broadest sense, considering the social and political implications. A significant focus is placed on infrastructure management, taking global models as examples. This podcast intends to be a resource for knowing good practices related to mobility.

Urban Exchange: Cities on the Frontline

The Urban Exchange podcast is a collaborative project to foster mutual inspiration for cities and city-makers. Based on interviews with city leaders, the podcast aims to be a virtual meeting point for city leaders to exchange successful practices. It includes only four episodes, issued irregularly, but is backed by two key institutions: the Resilient Cities Network and Smart Cities World. The two organizations cooperate on specific urban issues, in the belief echoed in the podcast that cities are indeed on the frontline for solving major contemporary problems and that cooperation is the way forward to fully harness this potential.

Eurocities

The Eurocities podcast, released monthly, is a conversational podcast informing about the most relevant steps of the cities part of the Eurocities Network. This network has been operating primarily in Europe since 1986 to foster relations between cities and the EU. With more than 200 of Europe’s largest cities from 38 countries, Eurocities aims at shaping the EU’s urban policies. The network creates synergies between cities to have shared and clearly defined goals in this same direction. The podcast is a valuable tool to get to know the main European urban actors through interviews with the mayors of some key cities in Europe (such as Rotterdam, Nantes, and Utrecht) and get insight into the action of this leading urban network.

Honorable mentions

Podcasts on urban issues are varied, and many of them are also very widespread and listened to. They address particular urban matters, such as transportation, architecture, landscape, urban planning, etc. Talking Headways is a very dynamic podcast that has been in production for years and systematically deals with transportation and infrastructure, exploring the relationship between transportation, planning, and quality of urban life. Among the podcasts focusing on urbanism and architecture, 99% Invisible is a reference, ambitioning to reveal the secrets and stories behind urban design, from urban furniture to major skyscrapers. The Smart Community podcast is a weekly show about the big issues of smart cities applied to the communities that inhabit them. Urban planning is the topic of the American Planning Association podcast (APA) that bimonthly addresses interesting case studies of American cities.

Last but not least… the City Diplomacy Student Podcast

And finally, be sure to check out the City Diplomacy Student Podcast. Episodes of this podcast, now in its fifth season, are produced by students from Sciences Po – Paris School of International Affairs (PSIA) and Columbia University, under the guidance of Dr. Lorenzo Kihlgren Grandi, director of the City Diplomacy Lab. Each episode provides a pedagogical and analytical insight into one of the key players in city diplomacy. -

Executive education for African municipal officers

How can city diplomacy empower African cities? The City Diplomacy Lab partners with the International Association of Francophone Mayors (AIMF) to launch the first two executive courses for African cities’ officials. They will take place at Columbia Global Centers | Tunis starting next month.

Course 1: MIXED MIGRATION AND CITY DIPLOMACY IN AFRICA: KEY ISSUES, CONCEPTS, AND TOOLS FOR ACTION – week of May 9, 2022

Course 2: DRIVING THE DIGITAL TRANSITION IN YOUR CITY: HOW AFRICAN LOCAL AUTHORITIES ARE APPROPRIATING THE SMART CITY CONCEPT – week of June 6, 2022

Both courses aim to strengthen the professional skills of participants. As a result, they will be able to apply the skills acquired in the design and management of strategies and projects upon their return to their municipalities.

-

Smart city standards: a collaboration challenge?

Cities today are called upon to deploy the potential of smart city policies. To guide municipal action, several international standards for smart cities have emerged. Nevertheless, the sheer number of players on the scene makes a unifying effort increasingly necessary.

By Emanuele Sala

The United States Conference of Mayors claims that no fully developed and executed smart city exists anywhere today. The definition of the concept itself is still evolving, and financing strategies and models are unclear. In this general setting, many local leaders are feeling smart city fatigue, as they are trying to make sense of the barrage of pitches from vendors and private consultants now populating this field.

The only way out of this effort seems to be the use of standards for smart cities, which should ease the work at the local level and make solutions more interoperable and marketable. However, the reality is somewhat different. Multiple actors crowd the stage of smart cities’ standards, making a single codification more difficult. Some valuable experiences emerge from intermediary actors ready to support the implementation of smart cities. However, to achieve consistency in standardization and measurement, the path of cooperation needs to be seriously explored.

The evolving concept of smart city

The International Telecommunication Unit (ITU) defined the smart city as “an innovative city that uses information and communication technologies (ICTs) and other means to improve quality of life, the efficiency of urban operation and services, and competitiveness while ensuring that it meets the needs of present and future generations with respect to economic, social and environmental aspects” [1]. This definition, adopted by the United Nations, emphasizes the ultimate goal of smart cities policies, namely improving quality of life. But it also reveals the breadth of issues that smart cities policies address. Therefore, the implementation is incremental and involves many public and private actors, infrastructure providers, product vendors, or policy-makers in constant communication and exchange. The exchange occurs only on the condition that the actors speak a common language. In other words, they must use the same consistent technical rules stipulated by technical standards. Cities need to refer to international standards to adapt to novel technologies or comply with international requirements.

A technical standard is an established requirement to repeat common tasks, providing regulations and conditions to adapt to the bespoke needs of the implementation.[2] The International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) describes standards for smart cities as “the first step towards the holy grail of an interoperable, plug-and-play world where cities can mix and match solutions from different vendors without fear of lock-in or obsolescence or dead-end initiatives” [3]. Suppose a city has the tools to develop a technical architecture or procure it through a specific vendor. In that case, it might become dependent on a technology that is not shared or bound to a sole vendor, with all the risks that could follow. Smart cities need a common language, and international organizations for the standardizations are there to codify this common language.

A composite picture of the international standardization for smart cities

The International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO), the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) are the four most widely recognized international standard organizations. They each produce thousands of standards based on the technical features of currently available technologies. They address multiple urban domains: energy, economy, environment and climate change, finance, governance, health, housing, population and social conditions, telecommunication, transportation, urban planning, water, etc.

However, as Attour et Aller refer, standardization is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for service interoperability. A functional application of standards implies cooperative solutions from the major business players and industrial players from different sectors (IT, telecoms, energy household appliances, mass retailing, etc.) under the strong incentive of political authorities.[4]

The role of two regional networks in the implementation of smart cities projects

The essential cooperation between suppliers and city administration is facilitated by an ever-growing number of city networks that try to make solutions interoperable and scalable. In particular, two of them, the World Smart Sustainable Cities Organization (WeGO), based in Seul, and Open and Agile Smart Cities (OASC), based in Brussels, have developed original instruments to help cities apply the fittest solutions. The first one is mainly present in Asia and Africa and features 158 members, while the second one’s 150 members concentrate in Europe and South America.

WeGO promotes the Smart City Driver, a framework conceived to help cities plan, finance, and deploy smart city projects. The framework includes three interconnected tools (Activator, Solution Finder, Project Implementer). The Activator allows to discover, plan and exchange smart initiatives. The Solution Finder is used to obtain a bespoke diagnosis of urban challenges and match cities’ needs with the solutions available for export by smart city strategic partners worldwide. The Project Implementer provides financial support and technical assistance for the transformation. These tools aim to create a junction to exchange the needed basics in setting up smart cities projects.

OASC proposes to its members the Minimal Interoperability Mechanism (MIMs), tools based on open technical specifications (a specific level of standardization that covers the technicalities needed to implement products and services), allowing cities to replicate and scale solutions everywhere. MIMs unlock the benefits of interoperability by taking minimal common ground to implement the smart cities standards. The further implementation can be different, but the basic interoperability points use the same interoperability mechanism. OASC also established a marketplace where solutions come together, providing the instruments for procurement and deployment to businesses and local governments.

These organizations connect cities and businesses with the world of standards, making them accessible and more immediately applicable to smart cities projects. Nonetheless, interoperability and scalability are desirable only if it is possible to benchmark different solutions and evaluate their actual impact through measurement indicators.

Key performance indicators to measure smart cities’ initiatives

With increasing budget restrictions, knowing the best opportunities to achieve specific objectives is paramount. Many different measurement frameworks exist to make solutions more quantifiable and adaptable. According to the OECD report on measuring smart cities’ performance, many institutions and organizations, even cities, developed their measurement frameworks and reported more than 1152 indicators of measurement.

Amongst them, the ISO has developed measurement frameworks for sustainable, resilient, and smart cities and smart infrastructures indicators. The ITU has developed a framework for KPIs, thanks to the project United for Smart Sustainable Cities (U4SSC), a UN initiative supported by ITU, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), and the UN-Habitat. CityKeys is an initiative for the measurement promoted by Eurocities, addressing only the European dimension differently from the counterparts ISO and U4SSC.

We see many indicators covering many different dimensions and different reaches. This variety of indicators raises a problem for the uniqueness of the language: too many regulators make a unified understanding more complex. A single measurement system is the first step in enabling exchange between cities and creating a single market for solutions.

Cooperation as a means of achieving unity in standards for smart cities

The amount of activity in smart city standardization is overwhelming. That is for the breadth and scope of smart city activities and because standards bodies are still trying to understand how they can best operate. Another reason for the equivocal nature of standardization is that each stakeholder wants to have a voice in defining standards, their implementation, and their measurement. Standards for smart cities describe today’s technologies and dictate the direction for future developments. Organizations that engage in standards applicability and facilitate their adoption, as OASC and WeGO, might also want to lobby in standards-setting. The same local governments, which are often disadvantaged in relation to the national scale, see in these organizations useful means to gather consensus around some standards and make them accepted.

Such multilevel governance made by local governments, intermediary organizations, and international organizations is beneficial if it first ensures the funding and tools necessary without imposing inappropriate priorities or redundancies. In this connection, the duplication of indicators remains a severe obstacle to a unique implementation of smart cities tools.

The only path to obtain a unified, fungible language and then relieve the pressure on mayors seems to be cooperation amongst standardization bodies and cities, with the involvement of the latter’s globally recognized institutional channels.

[1] ITU, 2014. Smart sustainable cities: An analysis of definitions. Focus Group Technical Report.

[2] City of New York. 2018. NYC Open Data Technical Standards Manual.

[3] ISO. International Organization for Standardization.

[4] Attour, A. and Rallet, A., 2014. Le rôle des territoires dans le développement des systèmes trans-sectoriels d’innovation locaux : le cas des smart cities. Innovations, 43(1), p.253.

-

The Mayors’ Action Platform: a new instrument of urban governance

A new platform for exchanging good urban practices and improving the governance of the cities across the globe. The Mayors’ Action Platform was launched last September by the Geneva Cities Hub.

By Emanuele Sala

The Geneva Cities Hub[1] (GCH) introduced the Mayors’ Action Platform (MAP) in September 2021 to ensure continuity to the Geneva Declaration of Mayors. The platform aspires to be an operational tool for mayors and city policymakers to peer exchange and share solutions and best practices addressed by the Declaration of Mayors’ principles themselves. In line with the SDGs and the New Urban Agenda, the Declaration covers themes as the construction of resilient cities, the promotion of environmental, energy, transport sustainability, and the reduction of urban inequalities. It was adopted by the mayors of the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) during the first Forum of Mayors in 2020.

One of the specific objectives of the Geneva Declaration of Mayors is to establish a tool to turn its principles into reality through ongoing exchange and mutual learning. The MAP joins other similar platforms in establishing a polycentric model of governance for cities. Such participatory frameworks emphasize a shift in city policymaking based on the action of urban platforms and best practices. Despite the greater flexibility and the undeniable benefits of these institutional frameworks, more incentives to foster participation should be considered.

Benefitting from the exchange of best practices

The exchange of best practices is a fundamental means of city diplomacy and accrues benefits both locally and internationally. The exchange of knowledge between mayors has shown to be particularly effective, as municipalities learn from each other more than any other single source[2]. Eddy Adams, Thematic Pole Manager from the European knowledge-exchange program URBACT, reports that the exchange of best practices at the international level results in greater prestige, raising the city’s profile and showcasing the successful initiatives to potential partnering actors. Even the most reticent local stakeholder is more persuaded at the local level when a good practice is recognized internationally. Thus, external recognition can result in internal credit. Among the technical advantages, the codification needed to share best practices is of high value to understand even internally, dynamics that might be overlooked. Accordingly, codification makes the trajectory of the implementation clearer for everyone.[3]

This last point highlights that the pure exchange of good practices is only a starting point for an effective policy transfer: it is paramount to make them interoperable and adaptable in different contexts and conditions. For this reason, to become an effective tool for urban development, such platforms should be equipped with precise internal systems to assess the relevance of the proposed practices, both for the specific objectives and the effectiveness of the results. Every shared practice should make a clear link with the issues it tries to resolve and the outcomes it intends to reach, based on quantifiable and identifiable outcomes. Moreover, to facilitate transferability, they should support local governments in codifying best practices to identify a transfer potential that other stakeholders can exploit.

In this respect, the Mayor’s Action Platform sets few limits concerning the rules of acceptance of shared practices due to the broad extent of the themes included in the Declaration. The inclusiveness of the platform is thus favored over a strict selection of the practices. However, the platform offers a form for codifying best practices, making shared practices readable and uniform, and clarifying effects and outcomes. The form requires cities to identify which principle of the Declaration they are addressing with a specific policy and how citizens’ participation shaped the different phases of its implementation. A final evaluation of the impact and the effectiveness of the practices closes the form.

The value of urban platforms for city governance

The Mayor’s Action Platform is a tool that can be ascribed to the logic of polycentric governance instruments. The political economist Vincent Ostrom defines these instruments as governance arrangements regulated by patterns of interaction amongst independent units operating at different geographical scopes. These actors mutually monitor, learn, and adapt strategies with reciprocity and trust[4]. In recent research focused on the Covenant of Mayors, Ekaterina Domorenok points out how the logic of “governing through enabling” municipalities with mutual knowledge and reciprocal links often results in collaborative networks.[5]

The voluntary commitment of the members highlights the shift from city policymaking in a command and control style to a policy change driven by networking, coordination, and peer learning. On the one hand, such institutional shapes ensure great flexibility, light structures, and high interoperability, and here lies part of the success of platforms and networks for urban practitioners. On the other hand, more substantial incentives for a sound policy codification and implementation and more explicit tie-in dynamics might be desirable in the next future. Providing support in best practice codification and establishing contacts among city experts and administration is a good basis for instruments that could evolve to become fundamental hinge points in city diplomacy.

In this connection, the MAP shows potential key success factors, particularly its proximity to the United Nations institutions. The European members, for example, that may be targeting more intensively their continental dimension than the wider international one, could benefit from the contacts that the MAP could provide with other cities worldwide and with the international institutions based in Geneva. Conversely, other UNECE and non-UNECE cities could establish connections with European cities and the international institutions based in the Swiss city, with its historical presence of influential global actors.

[1] The Geneva’s Cities Hub is the primary promoter of the platform. It was created by the City of Geneva and the Canton of Geneva, with the support of the Swiss Confederation, the UNECE and the UN-Habitat. The specific objective of the GCH is to offer support to cities and city networks by connecting them together and with the international institutions hosted in Geneva.

[2] Campbell, T. (2001). Innovation and Risk-taking: Urban Governance in Latin America. In A. J. Scott (Ed.), Global City-Regions. Trends, Theory, Policy (pp. 214–235). Oxford University Press.

[3] Adams, E. (2019). It is time for cities to share their good practices now, more than ever. Retrieved 22 January 2022, from https://urbact.eu/it-time-cities-share-their-good-practices-now-more-ever

[4] Ostrom in Domorenok, E. (2019). Voluntary instruments for ambitious objectives? The experience of the EU Covenant of Mayors. Environmental Politics, 28(2), 293-314.

[5]Domorenok, E. (2019). Voluntary instruments for ambitious objectives? The experience of the EU Covenant of Mayors. Environmental Politics, 28(2), 293-314.

-

Katowice to host the 11th World Urban Forum

“What kind of cities are needed to support the future of humanity? How do we envisage and reimagine the future of cities? What do we want our cities to look like?”

By Emanuele Sala

The World Urban Forum, the main global conference about the future of urban governance, will try to address these questions in Katowice, Poland, from 26-30 June 2022. The 11th edition, titled “Transforming our Cities for a Better Urban Future,” will focus on tools and policies to pursue sustainable urbanization, counting on the expected presence of thousands of representatives of national, regional, and local governments, academics, business people, community leaders, urban planners.

This global event aims at providing participants with an opportunity to share experiences, create networks, and hold debates about pressing issues facing cities and communities in the light of the 2030’s Sustainable Development Goals and the New Urban Agenda. Through high-profile debates, roundtables, assemblies, and informal meeting opportunities, the 11th WUF links the theme of urban sustainability to the growing role of cities in providing solutions to deal with pandemics and the environmental crisis.

Twenty years of World Urban Forums

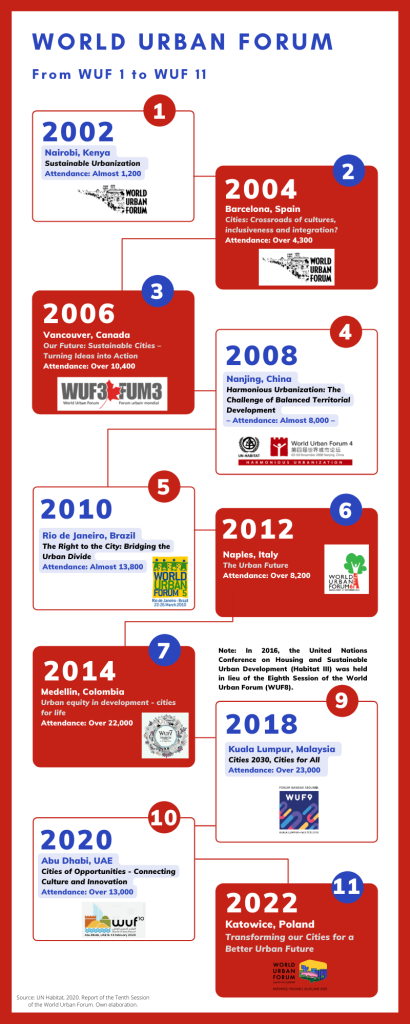

The WUF has operated since 2001, under the aegis of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), holding biannual conferences hosted by diverse cities. An overview of the past editions, host cities, themes, and participants can give an idea of the commitment of the institution, which has become “a platform to capture knowledge, innovation, and creativity for sustainable urban development” [1]. The primary outcome of the conference is a final declaration, providing general recommendations around which a substantial consensus was reached during conferences and debates.

From the data of the last five editions[2], there is a good gender balance in all the conferences, as well as a wide variety of functions covered, including academics, public administrators, and private sector operators. However, a large gap can be observed between the number of participants from the host countries and the rest of the world. This ratio, in some cases, reaches the figure of 1:1. The differentiation in the choice of the host cities counterbalances this predictable dynamic, ensuring a high level of representation from all continents throughout the various editions.

The choice of Katowice: global issues meet local solutions

The choice of the Polish city, which hosted in 2018 the UN Climate Change Conference COP24, is relevant. The city is a pole of coal extraction and steel production in a region where the carbon economy is still a strong reality. By contrast, the city administration and the community itself are incrementally transforming the city to make it greener and more sustainable. The choice to hold this event in Katowice gives value to and to learn from the city’s good practices.[3]

This choice is part of a trend that can also be observed in previous conferences: it is the case for WUF7 on urban inequalities and divided cities, held in Medellin, a city that has developed original experiences in urban safety policies. WUF5, in Rio de Janeiro, focused on the idea of the “right to the city,” widely studied and promoted in Brazilian cities.

The idea of drawing a link between the theme addressed and the host city reflects the principles at the heart of the conference. It emphasizes an awareness of the uniqueness of each city, together with a recognition of the value of sharing good practices and exchanging knowledge. To ensure that this exchange is accessible to all stakeholders, UN-Habitat publishes a detailed report of the event to account for the outcome of the proceedings.

The value of cooperation to face an uncertain urban future

The event, which has seen the number and the profile of participants grow over the years, was born and thrives on the assumption that the future will be increasingly urban. However, the coronavirus pandemic is a stark reminder that this urban future is uncertain. Hence, cities should be prepared and equipped for it. City professionals’ discussion and mutual learning can point to this direction, and the World Urban Forum is establishing itself as a valuable space for it, as a hub of ideas, policies, and improvements for urban governments.

[1] UN Habitat, 2020. Report of the Tenth Session of the World Urban Forum. Abu Dhabi, p. 130.

[2] UN Habitat, 2020. Report of the Tenth Session of the World Urban Forum. Abu Dhabi, p. 33 – 35.

[3] Fuchs, R., 2018. Katowice: A European coal capital goes green | DW | 02.01.2018. DW.COM.

-

2022 Forum of Mayors

The Forum of Mayors is a platform for ongoing exchange and mutual learning where Mayors will present their efforts to tackle challenges in their cities. Cities will learn from each other’s best practices in the areas of housing and climate-neutral buildings, green cities and nature-based solutions, sustainable urban transport and safer roads, and smart urban development solutions.

The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE), the host institution of the Forum, commissioned Dr. Lorenzo Kihlgren Grandi, director of the City Diplomacy Lab, to write a policy paper on the impact of the Forum containing concrete proposals for its evolution.

-

Can local agriculture save the world?

From New York to Melbourne, from Paris to Cape Town, a growing number of cities worldwide are taking part in a global reflection on the future of local food and agriculture.

The impact of climate change and rising socioeconomic inequalities is forcing municipalities to design their food systems around sustainability and solidarity. Additionally, the world trade disruption caused by the pandemic painfully revealed a heavy dependence on international food supply chains, underscoring the need for local food production.

Held on December 14th, 2021, the first webinar in the New Utopias series explored major trends in local food systems, the social, economic, and environmental challenges to consider, and the concept of “cities as laboratories of innovation,” foregrounding their impact on the present and future of urban life.

Speakers:

- Liliana Annovazzi-Jakab, Chief of Section, UNECE/FAO Forestry and Timber Section – Forests, Land and Housing Division, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe

- Pamela Ann Koch, Mary Swartz Rose Associate Professor of Nutrition Education; Executive Director, Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education & Policy, Teachers College, Columbia University

- Filippo Gavazzeni, Head of Milan Urban Food Policy Pact Secretariat, Municipality of Milan

- Lorenzo Kihlgren Grandi, Director of the City Diplomacy Lab (Columbia Global Centers | Paris) (Chair).

Q&A session facilitated by: Aliénor de Thoisy, Sciences Po graduate student.

The City Diplomacy Lab organized this event in partnership with the Alliance Program, Columbia Global Centers | Paris, and the European Institute. Co-sponsors include Columbia Maison Française and the Institute for Ideas and Imagination.

-

3rd Mayors Summit on Living Together

The Metropolitan Municipality of Izmir and the International Observatory of Mayors on Living Together hosted the 3rd Mayors Summit on Living Together, which took place on December 7 and 8 (online), as well as on December 10 (on-site, in Izmir), at the occasion of the International Human Rights Day.

City Diplomacy Lab‘s director Lorenzo Kihlgren Grandi delivered the keynote speech at the Interactive City Dialogue on Living Together: lessons learned and perspectives for cities in the future, on Tuesday, December 7 at 15h45 CET.